I’ve come to this one grassy hill in Ramallah, off Tokyo Street, to place a few red anemones & a sheaf of wheat on Darwish’s grave. A borrowed line transported me beneath a Babylonian moon & I found myself lucky to have the shadow of a coat as warmth, listening to a poet’s song of Jerusalem, the hum of a red string Caesar stole off Gilgamesh’s lute. I know a prison of sunlight on the skin. The land I come from they also dreamt before they arrived in towering ships battered by the hard Atlantic winds. Crows followed me from my home. My coyote heart is an old runagate redskin, a noble savage, still Lakota, & I knew the bow before the arch. I feel the wildflowers, all the grasses & insects singing to me. My sacred dead is the dust of restless plains I come from, & I love when it gets into my eyes & mouth telling me of the roads behind & ahead. I go back to broken treaties & smallpox, the irony of barbed wire. Your envoy could be a reprobate whose inheritance is no more than a swig of firewater. The sun made a temple of the bones of my tribe. I know a dried-up riverbed & extinct animals live in your nightmares sharp as shark teeth from my mountains strung into this brave necklace around my neck. I hear Chief Standing Bear saying to Judge Dundy, “I am a man,” & now I know why I’d rather die a poet than a warrior, tattoo & tomahawk.

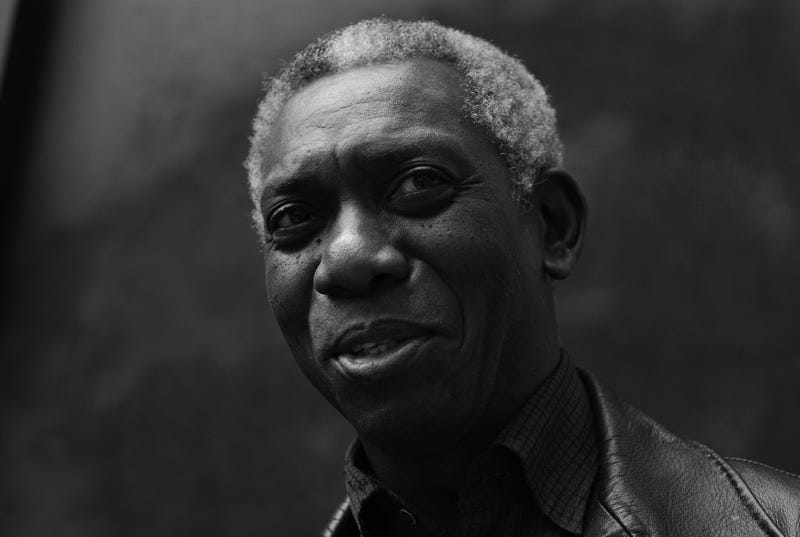

Yusuf Komunyakaa won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1994 for his wonderful collection Neon Vernacular. In doing so, he became the first (and last) Black man ever to win the prize for poetry. Too often is his name absent from lists of heavyweight poets of the last 40 years.

This particular piece was published in 2014 but it feels important to revisit it considering the ongoing genocide in Palestine.

The title carries a double meaning in that an envoy in poetry is a dedication to someone (or something) usually found at the end of a ballad. An envoy is also sent to conduct diplomatic relations with an independent nation. The title of this poem presents the painful juxtaposition of a hopeful acknowledgment of achieved statehood and a bitter farewell to that hope in the face of horrific mistreatment and an international blind eye.

The poem is a single unbroken stanza, which helps to drive its pacing. Similarly, the first four lines are so rhythmic with the play of o’s and e’s. “I’ve come to this one grassy hill/ in Ramallah, off Tokyo street/ to place a few red anemones/ & a sheaf of wheat on Darwish’s grave.” In structuring the lines in this way, Komunyakaa places a spotlight on the late great Mahmoud Darwish’s grave. For a moment, it seems that perhaps this is the envoy referenced in the title.

The beautifully alliterative line about the Babylonian moon is a nod to the idea of a stolen kingdom in Darwish’s poem A Horse for the Stranger. Now we begin to understand that this is less about Darwish and more about Palestine. Again we are treated to echoing sounds in balanced pentameter lines. “coat/ as warmth, listening to a poet’s song of Jerusalem” This is music.

Gilgamesh predates Caesar by at least 2000 years. The line featuring both heroes isn’t about an actual theft but about how history and the world replace us, and how few notice it happen. The plight here is that all are aware of the Palestinian fate. This is the source of the powerful line “I know a prison of sunlight on the skin.” This is the reality of Palestinians in an apartheid state and in that line, Komunyakaa is bringing reference to America’s history of imprisoning people of color in prisons of sunlight — both in slavery and in the post-slavery racist legislature.

The turn that happens here is fascinating. Our speaker makes note of a parallel to the treatment of the native peoples of North America, revealing themselves to be Lakota. This is another fine moment to mention that the poem’s speaker does not need to be the poet. Poetry does not need to be confessional snippets of true events to be truthful emotion. Whether Komunyakaa is Lakota is irrelevant (though with the horrific history of sexual violence against Black and Indigenous peoples in America, it is certainly possible) because this is about the parallel to a people told that the land that they were raised on, that that their great-grandparents played on as children is no longer theirs.

“Telling me of the roads behind & ahead” is a haunting way to invoke the cyclical nature of mankind. We leave death in our wake and we guarantee more death in our future, dust on both sides. The contrast to the wildflowers and the insects, all the life that exists in nature and our place as an agent of imbalance and death, underscores the harsh realities of this poem.

“The sun made a temple of the bones/ of my tribe. I know a dried-up riverbed/ and extinct animals live in your nightmares” Death transcends the people to an idea, a force that infects the minds of those that remain. This might be a reach for consolation by the speaker, but it is also a note on the implicit anxiety that comes with being human. The knowledge that sits constantly beneath our consciousness is that we are agents of death. That our success is built on the remains of species and cultures that we have wiped from the map. Outside of the idiots who champion this fact to feign personal relevance, most people cringe at this reality. This is the nightmare the speaker is reminding us of. This is the small victory that he can take.

On May 12, 1879, Judge Elmer Dundy ruled that noncitizen Indigenous Americans were persons. America had been a country for 100 years and it finally deemed a huge group of people living within its borders as humans. The speaker highlights this contrast to bring attention to the lack of similar distinction (insofar as the treatment of the people) for Palestinians.

“I’d rather die a poet/ than a warrior” ends the piece by honoring the death of Darwish and also a note to man’s greater potential: poets question, honor, and create while warriors kill and destroy. The speaker, having suffered much from the actions of warriors, chooses a different path.

Phenomenal. Thank you and this is another poet whom I have not explored as much as I could. I'll be re-reading this entry. I loved the rhythm of it as I read it but hadn't noticed clearly what he was doing until you described it. I appreciate that. BTW, your own comments belie your own poetry: We leave death in our wake and we guarantee more death in our future, dust on both sides.

Might borrow a line from a poem about a borrowed line in the future.

Appreciate your words, brother.