The wounded who could not speak English congregated around the bedridden every morning. Manuel, the nurse from some other ward, taught my father and others English word by word. Sometimes, phrases, the sloppy repeated English made sense—Because es porque. Porque is because. Dolor es pain, Yo soy es I am. I am. Otra vez, diganme.— Bee cause. Pain. I am in pain. English moved my father's tongue unlike Spanish. It stuck in his mouth, stumbled past his teeth. He dreamed he forgot Spanish and his tongue withered away. My father never told anyone about this or the scratching fear of his legs, under bandages and scars, never walking again. He didn't have words in English yet.

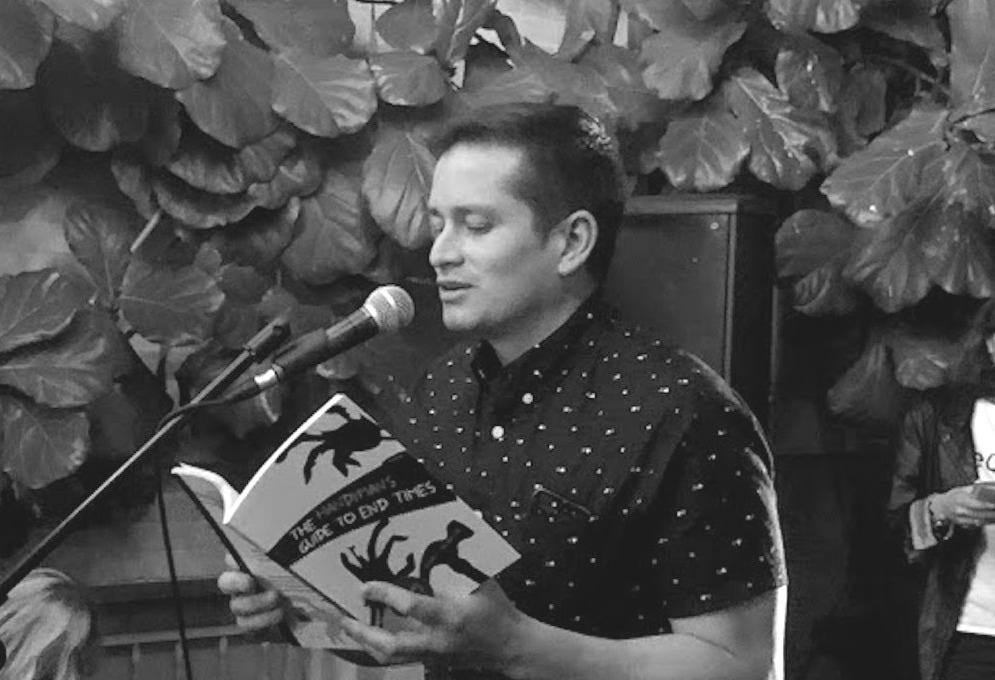

First, a shout-out to the great Joe Hutchison (@jhwriter) for the outstanding list of Coloradan poets to check out. Juan J. Morales was on that list. I picked up his book Friday and the Year That Followed and was glad I did. Morales weaves together stories family members told him and presents them with the magic of storytelling intact.

This piece follows a couple of pieces that present different memories from the Korean War. They are from the perspective of a Puerto Rican soldier for the US and paint a grim picture of death and indoctrination. The picture is one that is appropriate, considering that this was the generation of Puerto Ricans that overlapped with the release of West Side Story. The American idea of Puerto Rican people were violent immigrants who were in their country to kill or court their sons. Rereading these pieces with that in mind adds a new depth to the Borinqueneer soldier patrolling the Gojedo reeducation camp.

This particular piece takes us to a military hospital in Japan. The opening line reminds us that many Puerto Rican soldiers could not speak English, and this revelation coming after two pieces about their role in the war helps to highlight the bizarre liminal space between belonging and not belonging that Puerto Ricans occupied (and still occupy). The first four lines are all clear and straightforward. If you read each one aloud, it just sort of works. As the focus shifts to learning the language, the speaker uses clunky English phrasing to highlight the inherent confusion of a language learner. The fifth line, read out by itself, is a mess. You are now feeling what those soldiers felt as they sat trying to pick up the language of the land they’d just taken a bullet for.

The final line of the stanza is a powerful one. It references another poem in the collection in which the speaker sees, while battling insomnia, a bee in his room as a spirit who has come to feed on his sleep. He muses that bees are ghosts that are punishing humans in some way. This bee appears in this line, briefly bringing our thoughts back to ghosts. The statement that the soldier pieces together is sobering - because of pain, I am in pain. Because of the ghosts, I am in pain. Because of my part in the war, I am in pain.

The second stanza is focused on the difficulty of identity. “He dreamed he forgot Spanish and his tongue / withered away.” This fear is drawn as a parallel to the fear of never walking again. The loss of his language is the loss of his identity, and as a result is a loss of freedom of sorts. The final line of the second stanza is both humorous and sad: he couldn’t share this intimate fear of losing his language and identity because he hadn’t lost enough of his language and identity yet. He was capable of expressing physical pain but didn’t have the words to express emotional or mental pain. English becomes tied to that mental anguish — and maybe because English was tied to the acts he committed and the state of his homeland.