The midwife puts a rag in the dead woman’s hand, takes the hairpins out. She smells apples, wonders where she keeps them in the house. Nothing is under the sink but a broken sack of potatoes growing eyes. She hopes the mother’s milk is good awhile longer, the woman up the road is still nursing. She remembers the neighbor and the dead woman never got along. A limb breaks. She knows it’s not the wind. Somebody needs to set out some poison. She looks to see if the woman wrote down any names, finds a white shirt to wrap the baby in. It’s beautiful she thinks— snow nobody has walked on.

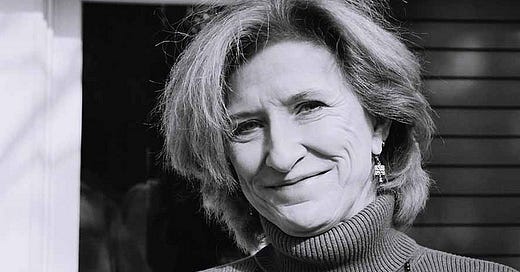

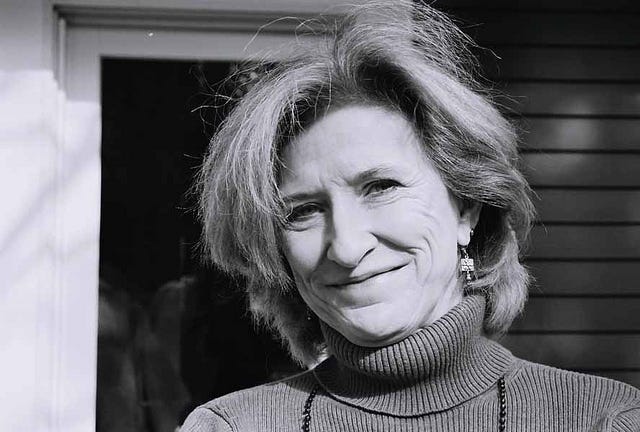

C.D. Wright was another poet who didn’t quite fit into the mold of a particular school or style. I could imagine many poetry feedback groups telling her she needs to edit her work to be less narrative, especially her early work. But it was that narrative style that created a voice unlike any other. Her poems were photographs of scenes we don’t often see: a poor, pregnant woman dumping a bucket of her shit in a hole or a young girl overhearing her father beating her mother (which was the poem I was originally going to analyze here but it comparatively too well known and my goal for Bare Patches is to expose you to something new).

This poem is five stanzas. The first is a simple couplet, but it packs a punch. We learn that a woman has died in childbirth and that a midwife is with her. The first line does most of the heavy lifting here, setting the emotional stakes. The second line might seem a bit random, in comparison, but it serves a different purpose. It highlights the pragmatism of our main character. This isn’t a time for an emotional breakdown and is likely possibly nothing new for her. The job is not done.

This is explored further in the second stanza. The midwife smells apples and actively seeks them. There’s a dead woman and (presumably) a baby, but she takes a moment to look for a fucking apple. This doesn’t come off as cruel or apathetic, but rather practical. She needs to fuel herself for what is coming. This serves as an opportunity to present the mother’s poverty— the only thing she has in her house is old potatoes.

Stanza three is pragmatic again. Another quatrain to represent the thoughts of the midwife. By keeping to this structure, the reader is able to better follow the events. Quatrains are structured, commonplace, and controlled. They are expected. By confining the thoughts to this structure, the reader is guided to trust the midwife’s expertise.

The fourth stanza is a break from the structure because it breaks the concentration of the midwife. The first line is short, sudden, and ends in a full stop. We are caught off guard in the same way as the midwife. Her calculated flow is interrupted, and as such the reader’s experience is interrupted. Three rapid, declarative statements. Three facts.

The final stanza brings us back to the structure, as the midwife finds something to wrap up the baby. In this moment, we are told for sure that the baby is alive. A bit of relief for having made it this far. The reader is similarly rewarded with a thread of optimism from the speaker — she acknowledges that the world of opportunity is available for the child, despite the rough beginning.

I love this. And I love it when women, particularly, remain true to their own school and style. This is how humanity evolves. Thanks for sharing, Mike.