Alan Dugan - Note of Quits

Don’t walk barefoot in the bathroom. There was someone in the mirror who I killed. God bless your hair-brush. God bless you. Though I swept up as best I could, there might be slivers of revenge left underfoot, so watch out for intrusion, love: be shod.

Last week, I mentioned that Louise Rosenblatt beat Ransom’s deep dive into Richards’ Practical Criticism by 3 years with her book Literature as Exploration. Rosenblatt presents the idea of her transactional theory of reading, placing equal importance on the reader and the text. This is very different from Ransom’s idea of the text as this sort of concrete concept, but it didn’t quite catch on in those early days. It would eventually inspire the wider Reader-Response theory (and we’ll get to that eventually), but she didn’t really dig that association and clarified her view through rereleases of her later book The Reader, The Text, The Poem. That book, by the way, is a fucking outstanding read. Here’s one gem from it: “Each individual, whether speaker, listener, writer, or reader, brings to the transaction a personal linguistic-experiential reservoir, the residue of past transactions in life and language.”

My approach to close reading is as heavily influenced by Ransom’s distant pragmatism as it is by Rosenblatt’s reminder that my experiences and peculiarities guide my eye and my ear in ways I am not always immediately conscious of. It’s not a product of only these two schools, but they are certainly pigments contributing to the final shade.

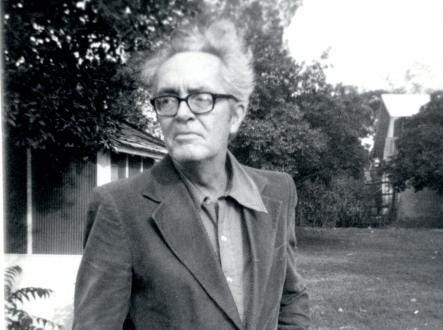

Today’s poem comes from Alan Dugan’s final collection of poetry, Poems Seven, published in 2001. I’ve spoken previously about poets who you can watch evolve through their collections over time, and Dugan is certainly a great example of that. His first collection, Poems, won him the Pulitzer for poetry in 1962. That collection is deserving and I already have a plan to chew through one of the pieces there, but it is very different in tone and style from his later work. Today’s poem would not only seem out of place in that first collection, it would seem to be from a different poet entirely.

The first line is trochaic and imperative. Opening with a stressed syllable on a word like “don’t” really hammers in the warning. The rhythm that Dugan creates (/˘/˘/˘/˘) is tucked into another sort of balance. “Don’t walk barefoot | in the bathroom.” There is a balance between the opening independent clause and the prepositional bit that comes after. It’s even echoed in the sounds. There is a visual rhyme to the words barefoot and bathroom, and a sharing of the a → oo vowel mouth feel. I don’t think that’s a real thing but I’m going with it. This line immediately creates tension because there is structural symmetry without logical symmetry. It feels balanced and complete but then our brains kick in and let us know we’re missing something. We want to know why.

The second line is just as declarative, but it comes just short of the balance. The first few syllables work together to twist where emphasis may normally have been. Let’s pick it apart. “There was someone in the mirror who I killed” is phrased passively and unnaturally. But in phrasing it this way, Dugan allows the sounds to play with one another. What would normally be iambic (there was someone in the mirror) mutates because of the s at the end of was and suddenly becomes “there was someone in the mirror.” It becomes a much more fluid, silky line. This makes that ending all the more intense. The d at the end of killed feels a hell of a lot more like a solid stop.

The third line is punchier. It feels rushed. Why bless the hairbrush? Did he use it to break the mirror? Did he use it to clean? There’s some sibilance between the blessings and the brush, but not enough to keep the line flowing. It feels weighty and significant, but fuck if I know why. And maybe that’s intentional. Maybe that obscurity is part of the mystery. We’re building a crime scene of sorts and the way the pieces play together isn’t immediately obvious.

Everything shifts after that “God bless you” bit. The next three lines are all a single sentence. The fourth line opens with a trochee (so did line three, but I forgot to mention it) that pulls some of the same rhythm from the beginning of the poem but now is a longer form. There is balance, but it’s reflective more than purely symmetrical. The line is 8 syllables, with “I” and short e sounds equally spaced from the midline. This gives the line a musical quality. That is continued with the following line, which has some slant assonance (I definitely made that shit up) between “underfoot” and the “could.” Try saying those two lines aloud, and imagine that there’s some folksy country music behind it. “Though I swept up as best I could, /there might be slivers of revenge left underfoot.” I know you can hear it.

The final line, in comparison to the rest, is strange. The idea of glass in the foot as intrusion feels strange. It’s as if the speaker places distance between himself and what has happened. There was a sort of huge, violent emotional climax and now he has allowed logic to slide back into place. His warning isn’t apologetic. It’s apathetic. The simple and practical advice offered in line one is now ornate and formal. Be shod? Who says that? It would be ridiculous if it weren’t so threatening. And that’s kind of the vibe of the entire poem.